Swatow is today of three prefectural-level cities of the Teochew region, the other two being Teochew 潮州 (Chaozhou) and Gek-yor 揭陽 (Jieyang). Being the Teochew people’s gateway to the world in the early 20th century, it was the port where our families embarked on their migratory journeys. As such the name Swatow rings familiar even for us who have never visited, and it has a special place in the heart of every overseas Teochews.

Until the 1850s Swatow was a nondescript settlement of only 5,000 people, many being fortune-seekers attracted by a European smuggling post on the islet of Masoo 媽嶼 (Mayu). With the aid of willing native agents, the foreigners not only sold opium here, but also carried away thousands of men - mostly victims of clan wars, kidnap, gambling and deception, to work in the sugar plantations on Cuba or the guano pits on the Chincha Islands. Raw anger against the Westerners was contained only by the protection of corrupt Qing officials.

Notwithstanding the character of trade, Swatow’s potential was not missed by more reputable opinions. Friedrich Engels noted in a piece written in October 1858 that Swatow had “at least some importance”, compared to the Chinese coastal cities the Western capitalists had forced open after the First Opium War. Two months later by terms of the Treaty of Tientsin that ended the Second Opium War, the United States demanded its official opening for trade and residence. Subsequently an American consulate was established on Masoo in January 1860 – an event many historians consider a milestone. However, Swatow would take a course of development unlike the other treaty ports.

The British followed the Americans to set up a diplomatic office in Swatow six months later, although their “Treaty of Peace, Friendship and Commerce” with Qing had given them the right to do the same in the Teochew prefectural city. But this could not be accomplished as its Consul George Whittingham Caine was unable to enter the city after the local gentry issued a public notice condemning the Qing mandarins for fearing and acting according to the bidding of the “foreign devils” (番鬼), and offering rewards of fifty silver dollars to anyone who kills the “head devil” (鬼頭) and one hundred silver dollars for anyone who captures him alive. After several failures, Caine finally passed the gates of Teochew’s principal city on 1 November 1865, but even the escort of heavy guard could not save the man representing the world’s largest empire then from being “treated with contumely and violence” during a brief stay. The defiance of the Teochews would never be tamed.

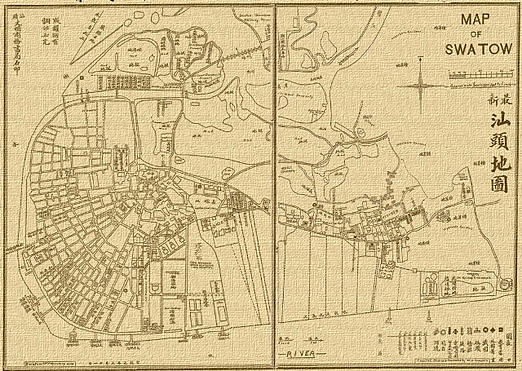

True to Engels’ assessment, Swatow grew at breathtaking pace right after the control of its port was removed from the hands of the Qing officials. It gathered merchants and petty traders from all counties of Teochew, but the seat of trade – where is now Swatow’s laoqiku 老市區 (old city district) – remained firmly closed to all foreigners. In the end the Americans and British were left with no choice but to build their permanent consulate premises in Kakchio 礐石 (Queshi), rocky stretch of land across the harbour. As Swatow’s population had climbed rapidly to upwards of 30,000 in 1874, its now well-known antipathy to outsiders limited the number of foreign residents to just 147.

Significantly, The Treaty Ports of China and Japan published in 1867 reported that in Swatow “trade is almost entirely in the hands of native or Singapore Chinese.” Whereas foreign capital was crucial to the commercial success of Canton (Guangzhou), Shanghai and Hong Kong, Swatow’s boom was fuelled almost entirely by the remittances of a diaspora, consisting of merchants, traders and labourers not just in Singapore, but also the Malay Peninsula, Siam (Thailand), Annam (southern Vietnam), Cambodia and Western Borneo, as well as key trading cities on the Chinese coast. However Swatow was not at all stunted. Fostered for over a century by fierce kin loyalty and a siege mentality, the Teochew network was rivalled by none in strength or wealth. By the 1880s Swatow was no longer just a port, but an emerging industrial centre with factories producing bean-cakes, oil extractions, flour, canned food, milled rice, matchsticks and fabrics, and heavy industry plants for ship-building and iron melting.

Now connected with electricity and public water supply, as well as by railway to Teochew city, light-rail to Changlim 樟林 (Zhanglin) and modern ferry services to other major towns, Swatow attained city status in 1919. Two years later it was separated from Thenghai 澄海 (Chenghai) county, which it was part of. However the city suffered a devastating blow on 2nd August 1922 when it was hit directly by a storm surge of at least 12 feet above normal whipped up by the Swatow Typhoon. The catastrophe took away 60,000, possibly as many as 100,000, lives in the city and its vicinity, and invoked worldwide concern, including a cable by American President Warren to his Chinese counterpart President Li Huan-Hung, expressing “the sincere sympathy of the American people as well as my own” over the “terrible disaster.” But still, the Swatow express train of progress could not be stopped.

Against the odds, the city recovered almost instantly with the generous support of Teochews abroad. American travel writer Harry Alverson Franck (in Roving Through Southern China) called early 1920s Swatow a place “busier, more prosperous air than most Chinese cities, even if it has also women quarrelling over peanuts dropped along the docks and beggars in the last stages of disease and starvation”. By the beginning of the next decade, Swatow was host to ten foreign consulates, two major hotels, six foreign banks and a list of big name trading and petroleum firms – amongst them being British American Tobacco Company, Jardine Matheson, Butterfield and Swire, Brunner Mond and Melchers, the Royal Dutch and Asiatic Petroleum Company, Standard Oil Company, Socony-Vacuum Company and the Texas Company. Stepping up to become an international centre of commerce, it commenced the construction of its first airport in 1929 and it became one of only nine Chinese equipped with automated telephone system in 1932.

Despite the Great Depression overwhelming the rest of the world, Swatow was now in a golden age. Between 1932 and 1937, it trailed only Shanghai and Canton in foreign cargo throughput handled and was China’s third busiest port. At the same time financial contributions from Teochew relations in Southeast Asia continued to pour in. In 1936 the Swatow Post Office handled overseas remittances totalling $40 million (in National Currency). The money provided livelihood for almost two-thirds of the households in Teochew and supported also a vibrant entrepreneurial culture. Although its population was only 280,000 in 1953, Swatow had 66 business and industry associations and 2,836 companies registered in 1949.

Joshua Lik says...

Good history to read in particular that part of Teochew before my birth in Swatow in 1930.

At the 1922 Typhoon 120 of the Lim clans in Tenghai District were drowned.

October 19, 2021